The insight that planning for more automobility is no panacea for social needs such as being able to reach places has meanwhile matured. The widening of roads does not ease traffic jams, faster and larger cars such as SUVs increase traffic unsafety in an urban context, large urban motorways in densely populated areas, such as the Ghent fly-over, place a huge burden on public space and affect the quality of the environment. Moreover, not only administrations, but also organisations and citizens are becoming more vocal about the externalities caused by the prevailing car dominance.

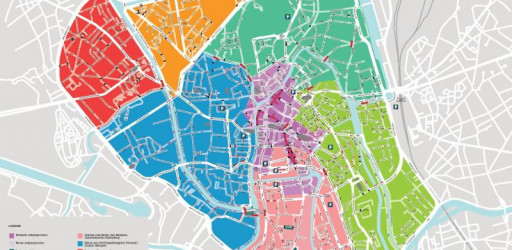

Meanwhile, the insight that planning for mobility cannot be seen separately from spatial planning is increasingly echoed in urban policy visions. Planning for mobility is meaningless if mobility does not provide access, as this access is determined at least as much by the geography of destinations in the urban fabric. A dense and diverse neighbourhood with a variety of amenities, workplaces and housing theoretically offers the most potential to accommodate daily trips in a sustainable way without much loss of time. If that neighbourhood is also veined with sustainable mobility infrastructure (high-frequency public transport, connecting bicycle bridges and bicycle streets, car sharing, ?), then a transition towards truly sustainable mobility and space use seems a natural outcome.

But is this dreamscape true, this imaginary or this mantra of the reachable or nearby city, well always, everywhere and for everyone? Preeminently in corona times full of lockdowns, curfews and distance, this question seems more relevant than ever. Thus, in cities worldwide (such as Brussels, Paris or Melbourne), the concept of the ?10/15/20-minute city? has been put high on the agenda. But is this policy vision also cashing in on its sustainability ambitions in practice? Does it take sufficient account of social issues of diversity, inclusion and equity, and the relationships that exist between ?amenity improvement? under a neoliberal impulse and social displacement effects? Who has the opportunities and resources to reap the benefits of this increased, sustainable, amenity? ?

Deze en andere vragen over sociale dispariteit in de context van stedelijke bereikbaarheid worden niet steeds even expliciet gesteld In shaping, implementing and monitoring ?sustainable? urban policies. Are there important frictions to be identified between dream and disparity? (How) can we identify spatial patterns of inequalities in mobility and accessibility? Which dynamics of disparity are insufficiently captured in current policies? (How) can the not-to-be-underestimated urgent challenge of making our mobility drastically sustainable be a positive story for every citizen of Ghent? (How) can we address these questions in an inter- and transdisciplinary way? Which international examples bring successful stories that can also support the Ghent case?

These questions are relevant in the context of various issues arising within the context of urban accessibility.